Citizen with a Movie Camera: The Ramon Williams Collection

Written by SSHMP on 08.10.2023

While most of the South Side Home Movie Project’s collections offer uniquely intimate footage of mid-20th century everyday life on Chicago’s South Side, rarely does the home movie maker’s gaze leave the subject of the family to depict the world around them. Donated to SSHMP in 2020, the Ramon Williams Collection is a significant exception. This collection of 302 film reels, our single largest donation to date, represents a never-before-seen visual record of Bronzeville authored by one of its few citizens with a movie camera.

With support from the Gaylord and Dorothy Donnelley Foundation and the Women’s Board of the University of Chicago, the preservation, digitization and cataloging of this historic home movie collection is underway at the South Side Home Movie Project. The first fully accessible reels are available to view on the Ramon Williams Collection site within our Digital Archive.

Ramon Williams: Bronzeville Citizen That Made Movies of Picnic

Ramon Williams, a Black IBEW electrician and film hobbyist, was an early adopter of amateur filmmaking and invested in documenting the Bronzeville community in which he lived, a historic district with a rich legacy of early 20th-century Black history and culture.

From the box labels in the collection and articles in African American newspaper The Chicago Defender, we know he filmed major Bronzeville social and civic events between the 1940s and 1960s. In September 1941, the Defender honored Ramon for filming the Bud Billiken parade earlier that summer by printing a short article, “He Made Movies of Picnic”, which includes a bio and a portrait of him.

In January 1942, the Defender printed “Century Cinema Releases 1941 Camera Cavalcade,” an advertisement to screen: the Bud Billiken’s Americanism Day Parade: the Royalites Fashion Show, the dedication of the South Side Community Art Center by Mrs. Eleanor Roosevelt, the 4th Annual Midwest Horse Show, and the Artists and Models’ Ball. Ramon advertised his services as the “Century Cinema News Reel-ette,” a name that signaled his intent to create newsreel-like films to be screened in his community so that his neighbors could rejoice in seeing positive, beautiful images of their youth, artists, political and cultural leaders.

Discovering a Treasure Trove of Moving History

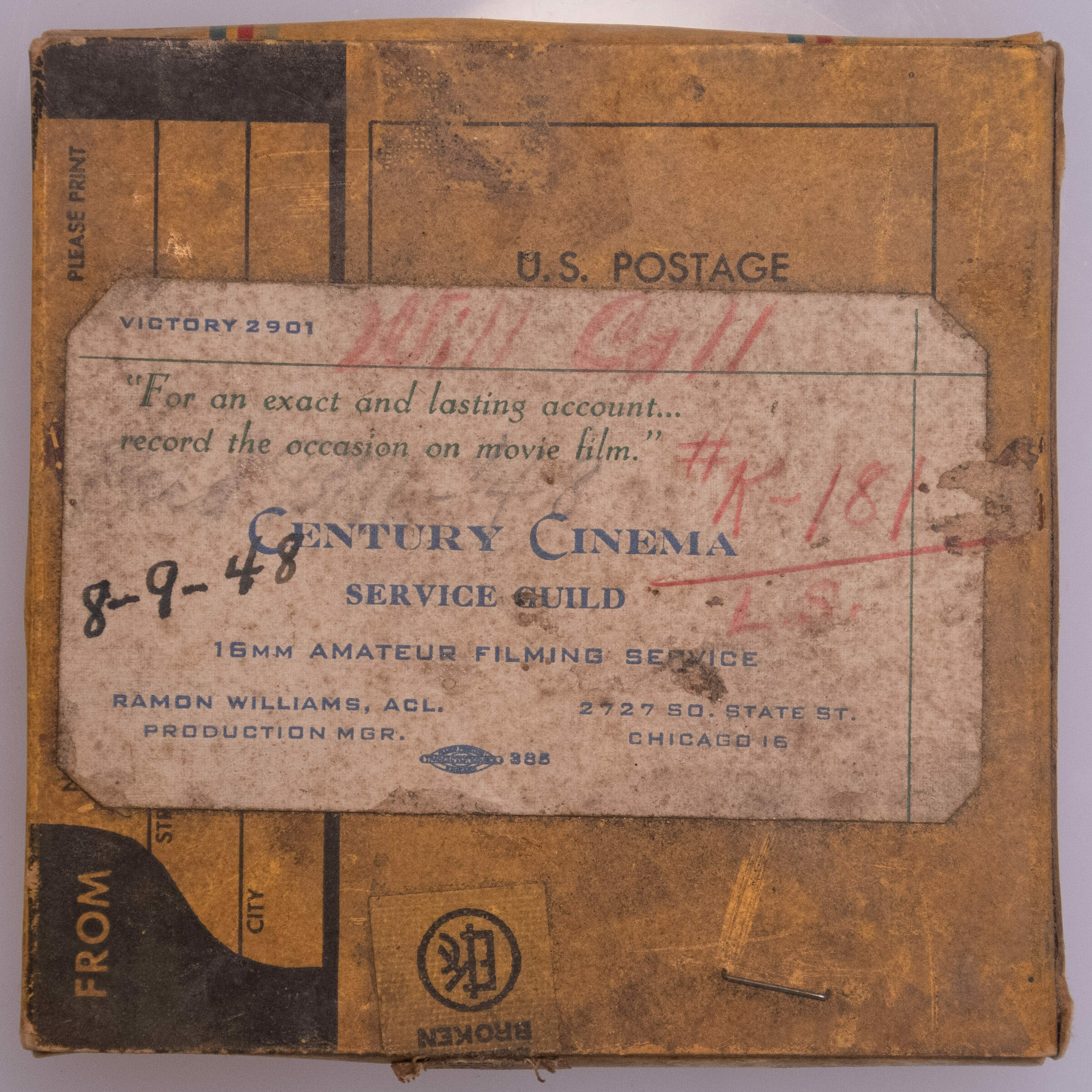

The very first box of film we opened gave us an idea of Ramon Williams’s technical and artistic mastery as a filmmaker and the uniqueness of his footage of Bronzeville’s social and cultural life in the mid-20th century. The box had his Century Cinema business card glued to it and was simply labeled “8-9-48.”

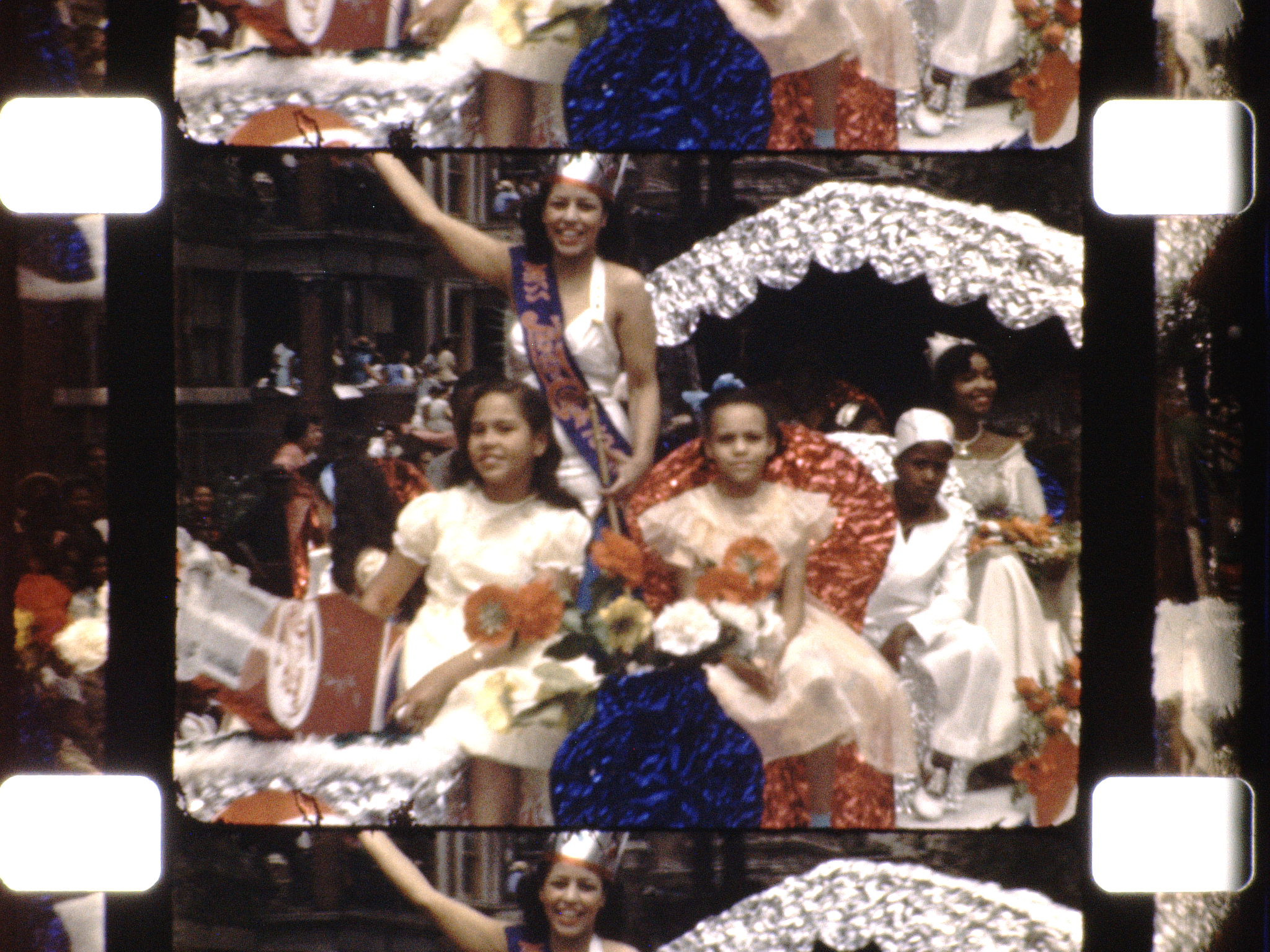

After careful inspection and digitization, we uncovered rare footage of the 1948 Bud Billiken Parade, the largest African American parade in the US, held since 1929. Ramon had filmed from the middle of the street, a prominent position from which to capture the procession of floats that carried local and national Black pageant contestants, advertisements for local Black businesses, cars decorated with the emblems of the churches and fraternal orders in the community, and performances by Black South Side youth. Over three and half minutes, the majesty of this parade unfolds on beautiful Kodachrome film, which has not lost any of its rich color since it was shot. The presence of his camera allows us to relive these past scenes from Bronzeville’s largest cultural celebration (a tradition that continues to this day) but also invites us to engage with the historical significance of that moment and be grateful it was documented by an intrepid filmmaker.

Bronzeville on Film

As one of the oldest collections we have ever received, and the only one exclusively focused on documenting the social and community life of Bronzeville, the Ramon Williams Collection will broaden the visual narrative and demonstrate how Chicago’s South Side was a fulcrum of Black social, cultural, and political life in the mid-20th century that influenced the nation and the world. Former Rep. Bobby Rush, who presented the Bronzeville National Heritage Area Act bill to Congress, described the area as “the birthplace for much of the African American community’s ingenuity, poetry, artistry and contributions to Chicago and the nation…From Ida B. Wells to Nat King Cole, Bronzeville is a birthplace of Black genius — genius that has had a lasting influence on our city, our state and our entire nation.”

The Ramon Williams Collection reveals a rich, complex narrative that encompasses the regular folks and familiar places that defined Bronzeville, beyond the legendary celebrated Bronzeville figures (Gwendolyn Brooks, Lorraine Hansberry, Nat King Cole), thanks to the work of local historians making the case for the neighborhood's historic status in recent years. Importantly, the films illuminate the world these famous Bronzeville residents inhabited: see reel entitled “New Year's Eve party at the Pershing Ballroom.” They also introduce people, places, and names that might otherwise be buried in history. In a broader sense, this collection, like most home movies in the SSHMP archive, offers an underexplored range of scenes and images that activate fresh, collective reflection on the ways in which people from historically marginalized groups – particularly African Americans and youth – have used the moving image to navigate the varied expectations of their families, peers, communities, and the broader society.