We Were There Together: Jacqueline Stewart on the Two Decades of South Side Home Movie Project

Written by Nicky Ni on

07.08.2025

for Read the NewCity Feature Here!

When Jacqueline Stewart [Newcity Film 50], professor of cinema and media studies at the University of Chicago, attended the first Orphan Film Symposium back in 1999, the nontheatrical films she saw there got her thinking how many similar home-movie collections there must have been in her neighborhood, sitting in dusty basements, yet to be discovered. A born-and-raised South Sider, Stewart took on the mission to find those hidden gems with the goal to preserve them and unveil them to the world, and in 2005, the South Side Home Movie Project (SSHMP) was born.

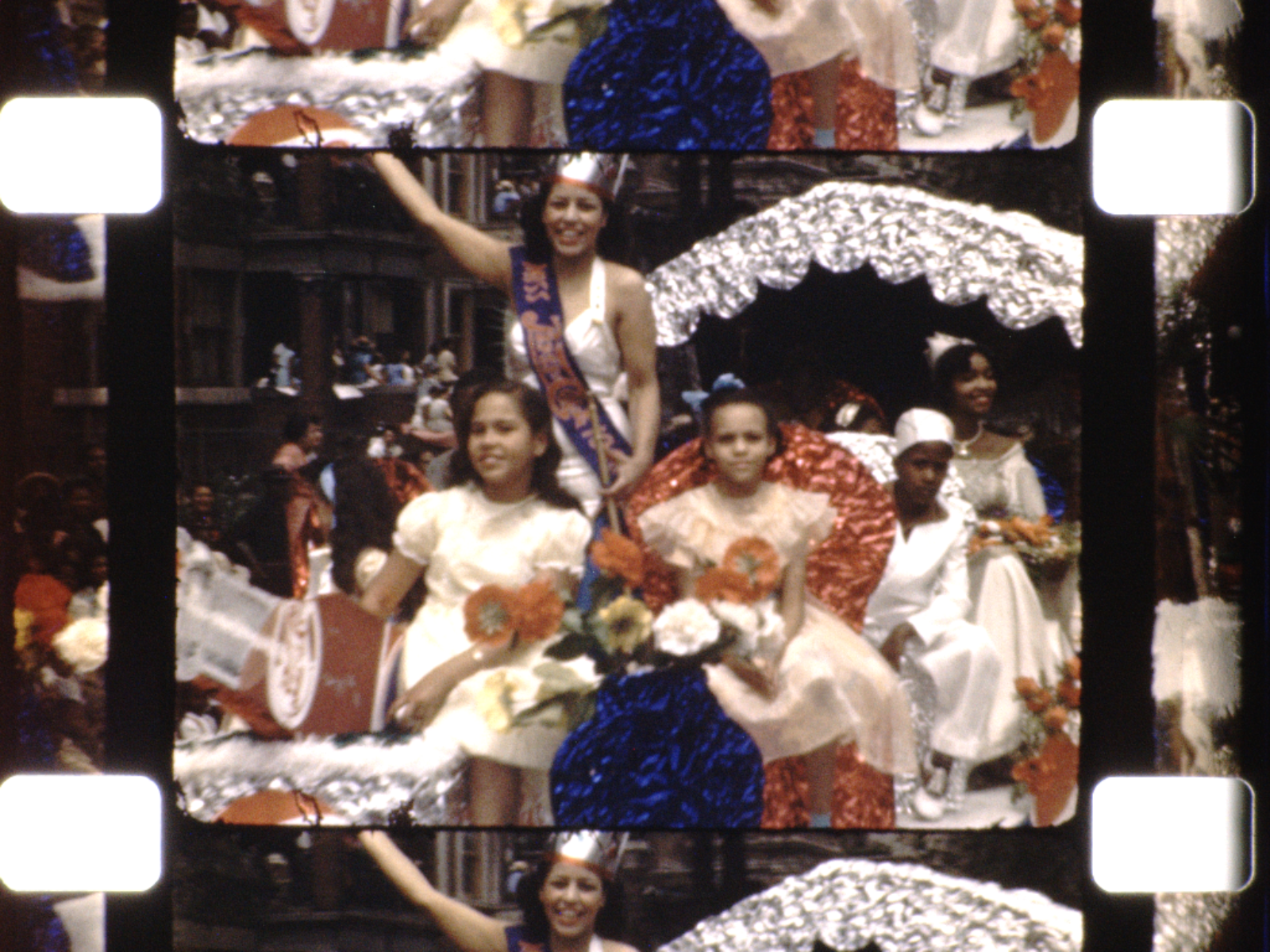

In the past two decades, the project has collected over a thousand reels, most of them 8mm, Super 8 and 16mm films from over forty families in the South Side. These films span decades from the 1920s to the eighties, and they are not only an intimate and vivid documentation of urban domestic life, but also precious archival material for film and Chicago histories. Making sure that these materials stay accessible is important for SSHMP, and over 700 home movies are globally accessible through its online portal.

Another side of this project lies in programming events that engage community and encourage creative reuse of its archives. SSHMP hosts community cataloging, unique screenings in which community members are welcome to speak up over the films to identify subjects in the film. The signature program Spinning Home Movies invites musicians, DJs and spoken-word artists to create unique soundtracks for clips they select, and to participate in post-event conversations.

This July, on the occasion of its twentieth anniversary, SSHMP will mount the exhibition “The Act of Recording Is an Act of Love” at the Logan Center for the Arts at the University of Chicago. The exhibition will survey the project’s two-decade history, one that would not have been possible without the continued support and trust from South Side communities that Stewart and her team have cultivated and maintained over the years.

Newcity spoke with Stewart in a video call and the interview has been edited for clarity.

How did the South Side Home Movie Project take off?

I had the opportunity back in 1999 to go to the first Orphan Film Symposium that was organized by a dear colleague, Dan Streible and others at the University of South Carolina. This gathering brought together scholars and archivists and artists to think about the vast body of nontheatrical films that were not receiving the attention and care they deserve. And it was there that I saw home movies shot by a man named Dave Tatsuno.

He and his family had been incarcerated during World War II at one of the many internment camps that Japanese Americans were forced into during the war. He had a camera in secret and he was shooting the staff of the cafeteria and kids sledding and people posing after church services. And it blew my mind. He was showing us everyday life persisted even in the most difficult of circumstances; people lived their daily lives as best they could. So it got me thinking, well, what are the other kinds of home movies that are out there?

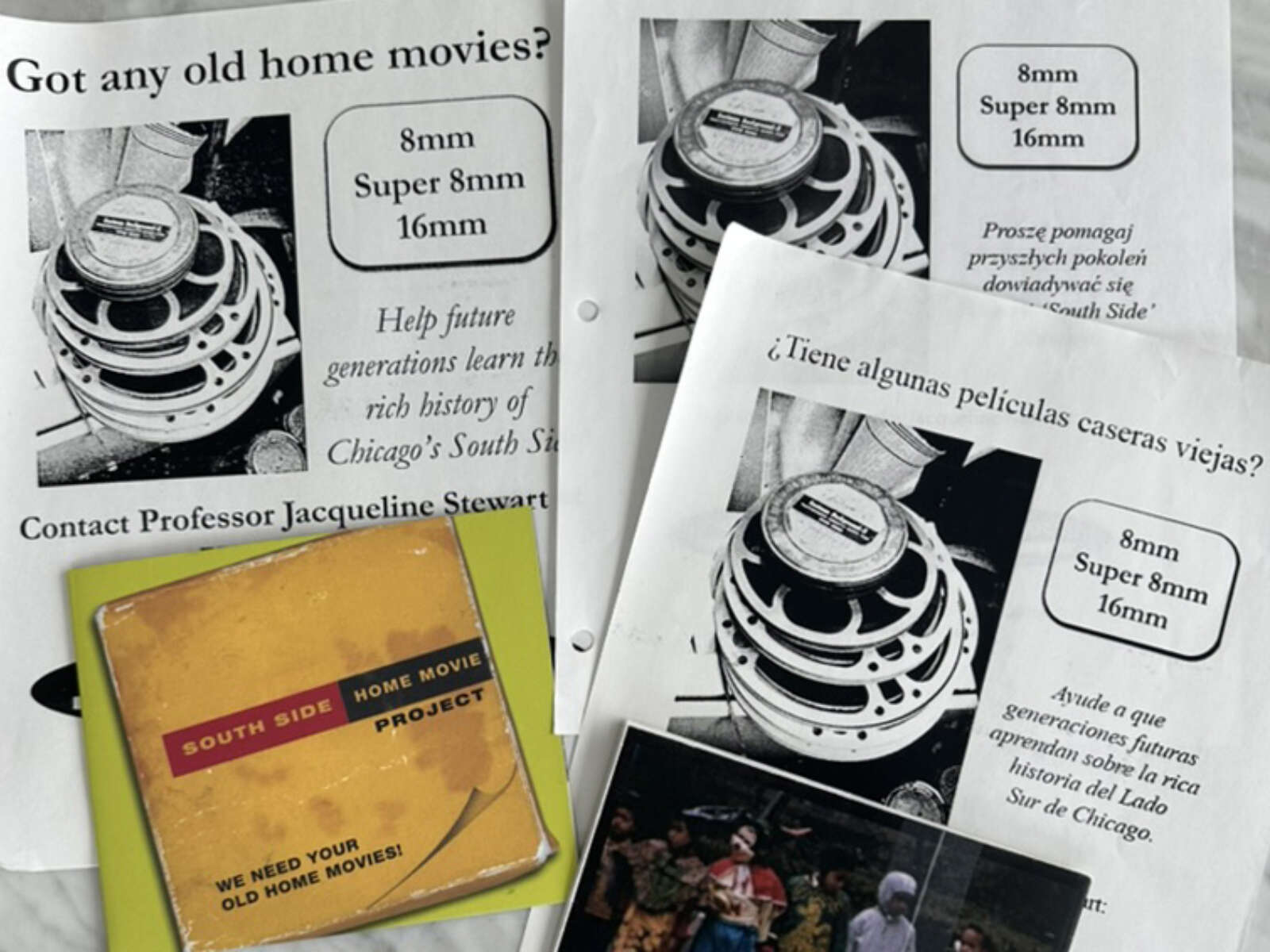

I was born and raised on the South Side of Chicago, and I thought it would be interesting to see what kinds of amateur films South Siders might have. In the summer of 2005, I put together a group of undergraduate students and some graduate students, and we started to develop the idea. We made some flyers, and we put them around the neighborhoods surrounding the university, just asking people, “Do you have old home movies?” And we were putting together the plans to digitize them so we could watch them and share them. And slowly, people really began to respond in big numbers. It turned out there were a lot of these materials, and I’ve been trying to build the archive ever since.

It’s really amazing that the collection started off as a project rooted in the community and would not have been possible without collaboration.

Totally. From the very beginning, it was clear to me that this had to be a collaboration. There have been so many elements of conflict over the years between the University of Chicago and neighboring communities, including the university’s role as an agent of urban renewal. So as someone who grew up on the South Side, I have always felt this kind of insider-outsider relationship to the university, and I knew that this project had to be something that people would trust. I did not want to act as though I was doing anybody a favor by taking their films out of their family’s hands and ensconcing them at the university. I wanted to build relationships with the donors. I wanted them to know that their materials were safe and their contents always available to them, and that the stories related to these really intimate and precious films are valued. As we digitize the footage, we have watch parties with the donor families, often at their homes, so that they are the first to see the transfers and so that they can have a moment to view and talk about images they typically have not seen in decades. I’ve tried to prioritize the quality of the relationships with our donors, more than just the sheer numbers of acquisitions that we take in.

What are some of the first ones that came to the archive?

One of the first is from JoAnne Gazarek Bloom. Her grandfather owned a tavern in Bridgeport and she has this incredible footage from the late 1930s of the baseball game that the tavern would host every year. Bridgeport has not had a positive connotation among many African Americans. Many people grew up being told not to go to Bridgeport because there was a real fear of anti-Black violence there. We did a screening really early on when we were showing these films, and at the same time we had African American families showing their footage. Conversations started to take place among people who had not been interacting with each other during the time the films were made. But they could see in the footage that there was so much affinity in the ways that families celebrated, or the ways that people decorated their homes, like, “Oh, my mother had that kind of lamp.” I could see that home movies created interactions among people that could allow for deeper conversation about what it meant to grow up in Chicago during this long period of rigid racial segregation.

That’s one of the most powerful aspects of what film can be, that it brings people together through shared experience and confronts us with history that’s hard to digest or at the verge of being erased. What are some of the other highlights in the collection? Any filming techniques you’ve observed across the board?

In the [Frederick] Atkins collection, there’s a short homemade zombie movie. There’s also an amazing stop-motion film from 1980 in which he’s taken his “Star Wars” figurines and staged the story of the movie. There’s one from the Patton family, where the kids did a little trick film where it seems like one person after another is coming out of a barrel, and then they all go back into that barrel, kind of a Méliès-style magic film. There are a number of reels that I love, where there’s double exposure that didn’t seem to be deliberate. What’s great about our catalog is that you can look up film techniques such as double exposure, “filming from car” or slow motion. To me, these formal and stylistic aspects are a helpful reminder that we should not look at these films only through the lens of nostalgia. Sure, because the reels were short, you are going to see people on their best behavior and performing joy.

And it certainly means so much, especially for African Americans who are looking at this footage, that we have visual records that counteract the images of pathology, crisis and violence that oversaturate media representations of Black people. But it also shows the ways that people engage with visual technologies, both as makers and as performers. The shaky camera reminds you that somebody is holding a camera. The interaction with the camera is part of what’s going on, that the camera is at the birthday party or at the graduation. It’s a way of understanding that people were always trying to keep up with the latest modes of self-representation and documentation, and that’s fascinating.

What’s also fascinating is all the events that you have produced that activate the collection. The Spinning Home Movies, for example, is just a brilliant idea.

A unique aspect of the South Side Home Movie Project is that programming has always been central to what we do. The films are mostly silent, so in our programs donors are invited to talk along with the films, and we encourage viewers to comment on what they’re seeing too. They’ll say, “This is my aunt at her high school graduation.” “That’s my cousin at one of our basement dance parties.” “This was my wedding in 1954.” That narration is absolutely critical to understanding the films. And there is this kind of community memory that gets activated. This is part of how we engage in community cataloging.

When the pandemic hit, we couldn’t continue this kind of live event, so we came up with the idea of asking a DJ to put together a soundtrack and livestream it with the movies, and we invited people to watch. And it just took off like crazy. The scenes of family and domestic life were really restorative and connecting for people, and they were posting comments the whole time, recognizing things and loving the music. So we kept it going with more and more DJs. And then we started working with musicians, composers, poets, filmmakers, asking artists to create new works inspired by the collections.

Are these successful programs going to concur with the upcoming exhibition, “The Act of Recording Is an Act of Love”? And how is the twentieth-anniversary exhibition going to unfold?

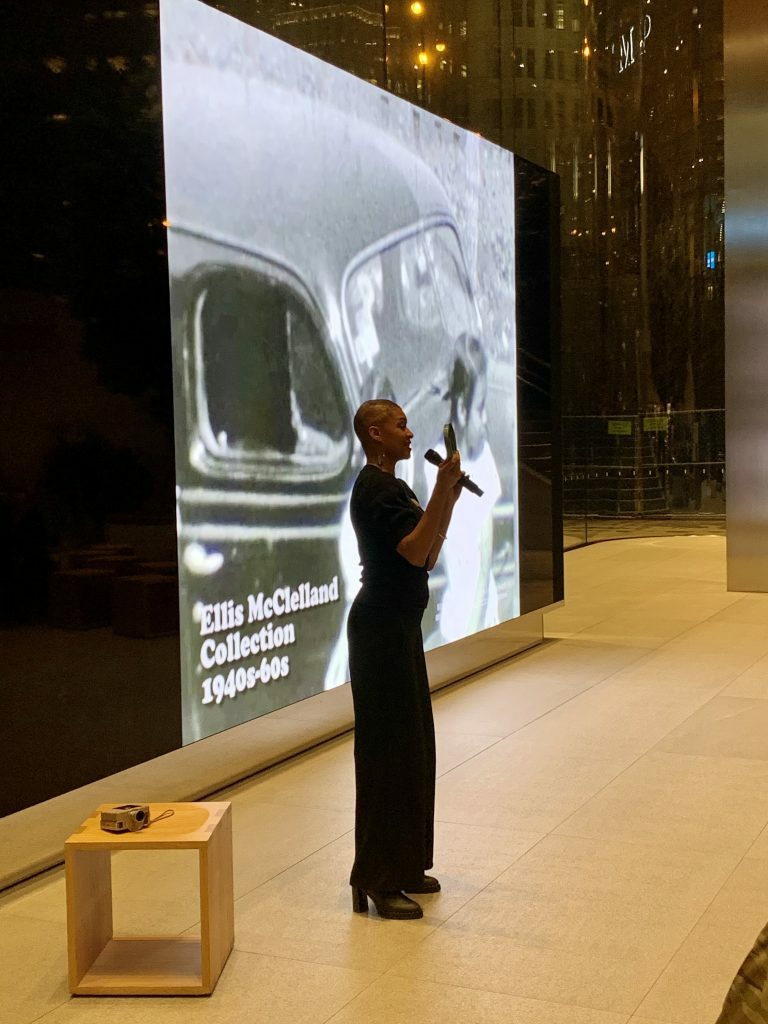

It’s really amazing to collaborate with our friends at the Logan Center for the Arts to present something in their gallery that helps us to celebrate those twenty years and to reflect on them. We’ll definitely be showing some episodes of Spinning Home Movies. We’re also going to show how the work has evolved from the earliest days, and how the preservation and digitization processes work. We are going to do a deep dive into some of our collections including our biggest, the Ramon Williams collection, which is extraordinary, and tell the stories of how they came to us and who these filmmakers were. There will be some areas where people can interact with the footage, including community cataloging, where we invite people to describe the footage. I’m also excited about some items we will display that were created by youth. Last summer, we had the honor to be part of the legendary Bud Billiken Parade. For the parade, we had a truck with LED screens showing footage from the archive of the parade over the years as the truck traveled down the route down King Drive. People were captivated by the images. It really helped them feel a sense of connection to that history and the pride of being part of its legacy today. In partnership with Arts + Public Life, the students from their Teen Arts Council took stills from South Side Home Movie Project films and created gorgeous hand-sewn banners inspired by those images that they marched through the parade. We’re going to display these banners in the exhibition! To me, these are unexpected creative reuses of the images we have in the archive. Lastly, of course, we’re going to have an area that screens lots and lots of home movies and spotlights donor families.

Are these successful programs going to concur with the upcoming exhibition, “The Act of Recording Is an Act of Love”? And how is the twentieth-anniversary exhibition going to unfold?

It’s really amazing to collaborate with our friends at the Logan Center for the Arts to present something in their gallery that helps us to celebrate those twenty years and to reflect on them. We’ll definitely be showing some episodes of Spinning Home Movies. We’re also going to show how the work has evolved from the earliest days, and how the preservation and digitization processes work. We are going to do a deep dive into some of our collections including our biggest, the Ramon Williams collection, which is extraordinary, and tell the stories of how they came to us and who these filmmakers were. There will be some areas where people can interact with the footage, including community cataloging, where we invite people to describe the footage. I’m also excited about some items we will display that were created by youth. Last summer, we had the honor to be part of the legendary Bud Billiken Parade. For the parade, we had a truck with LED screens showing footage from the archive of the parade over the years as the truck traveled down the route down King Drive. People were captivated by the images. It really helped them feel a sense of connection to that history and the pride of being part of its legacy today. In partnership with Arts + Public Life, the students from their Teen Arts Council took stills from South Side Home Movie Project films and created gorgeous hand-sewn banners inspired by those images that they marched through the parade. We’re going to display these banners in the exhibition! To me, these are unexpected creative reuses of the images we have in the archive. Lastly, of course, we’re going to have an area that screens lots and lots of home movies and spotlights donor families.

I’m imagining how folks at the parade last year were probably using smartphones to capture the parade, including the LED screen, producing yet another body of home movies, but in today’s visual and technological language.

How did you land on such a beautiful title, “The Act of Recording Is an Act of Love”?

Well, that was something that the brilliant musician and poet Jamila Woods said. Several years ago, she was putting together a performance at the Harold Washington Center on 47th Street, to perform her album “Heavn” from beginning to end, and she approached us about wanting some images that would be screened as a part of the performance. Themes like girlhood, sisterhood, water—there’s the love for the lake that she expresses in the music. It was actually that collaboration that later inspired Spinning Home Movies, the way that she brought these things to life through her musical work. “The act of recording is an act of love” is a comment she made during a post-event conversation. It was moving to the whole team.

There are lots of ways that we can think about home movies. We can see them simply as part of middle-class performativity. You know, people are showing off the things that they have attained, their homes, their cars, even their families—the conditions for good living that they’ve created. And what Jamila said really gave us an additional way to think about how there’s an act of care on display, and that recording these things isn’t always or only about showing off. The gesture of recording is also about the desire to memorialize people, of showing that you really see them and want them to feel seen.

“The Act of Recording is an Act of Love: The South Side Home Movie Project” opens on July 11 at the Reva and David Logan Center for the Arts, 915 East 60th, and runs through August 24. This exhibition also features furniture pieces by Chicago-based Norman Teague Design Studios. Special event “Digital Storytelling Initiative’s Mothering on Screen Film Series” is Sunday, July 13, 1pm at Logan Center Screening Room. 16mm filmmaking workshop with Thomas Comerford, Friday, July 19. A closing reception will be held on August 15.